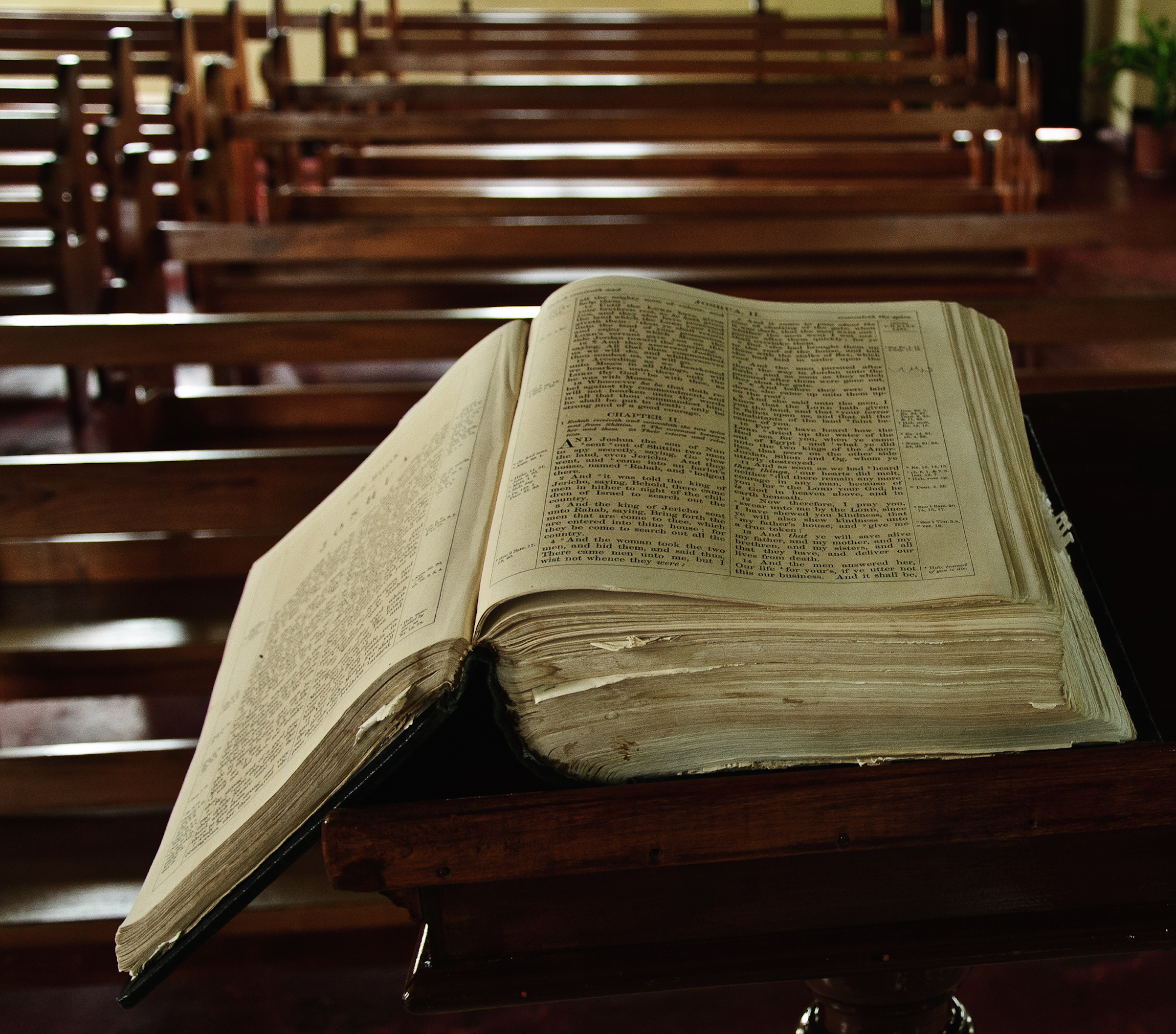

From the Chartist churches and ‘the religion of socialism’ to the evangelical roots of the anti-slavery societies, the language of reform had long been religious in character. Such rhetoric reflected both the cultural authority of the Bible and the religious genealogy of reformist politics. Looking back on the campaign years later, Annie Kenney described it as ‘more like a religious revival than a political movement’ and it is no coincidence that so many of its activists later took up preaching. 6 For ‘militant’ suffragists, in particular, the struggle could acquire a sacramental character: imprisonment was conceived as a ‘baptism’ and force-feeding as a ‘crucifixion’, while recruits spoke of their ‘conversion’ in terms that drew directly on evangelical life-writing. The educational reformer and suffragist Dorothea Beale had proposed a ‘Church League’ as far back as 1886, and the language and iconography of the movement drew heavily on Christian imagery. The Church League was the latest manifestation of an impulse that had burned through the suffrage campaign from its earliest days: a determination to fire the women’s movement with Christian mission, as a cause that was not only compatible with, but actively demanded by, the teachings of the Gospel. The spectacle, he confessed, ‘set some of us thinking’, and ‘made one feel that in sweeping all the women on the suffrage side into one category we are apt to blunder’. The Church Times had long been critical of the suffrage movement, but the spectacle of such ‘a vast number of Churchwomen’, raising the Cross of Christ in the cause of women’s enfranchisement, made a ‘profound impression’ on its reporter. Marching behind the processional cross, beneath a banner inscribed ‘For our Altars and our Homes’, followed the Church League for Women’s Suffrage (CLWS), an Anglican organisation led by the bishop of Lincoln. What caught the attention of the Church Times, however, was a cohort further down the procession, where a jostling array of college caps and birettas signalled the presence of the clergy. At their head, on horseback, rode ‘Joan of Arc’ and ‘General’ Flora Drummond, while a guard of ‘New Crusaders’ in robes of purple symbolised the ‘organisation of women in a Holy War’.

Nurses, graduates and local office-holders marched with factory girls, mill-workers and suffrage prisoners, alongside pageants depicting women of empire and great women in history. Mustering 40,000 women across seven miles of ‘gold and glitter and sparkling pageantry’, the march gave visual expression to the diversity of the suffrage campaign.

#GREAT COMPANY OF WOMEN SCRIPTURE FULL#

He had come to report on the Women’s Coronation Procession, the largest women’s suffrage march ever held in Britain and one of the few to draw together the full range of suffrage organisations. On 17 June 1911, a correspondent for the Church Times took his place on the Westminster Embankment. Ours is not a warfare against men, but against evil. The Women’s Cause is God’s Cause, and in the fullness of time He will give you the victory. In the strength of the Cross of Christ shall the cause of Womanhood be won, and before its radiance the powers of darkness flee. The churches, it is concluded, did not simply respond to changing ideas about sex and gender they were themselves sites of new thinking about the roles of men and women, forming one of the many tributaries that fed the flood-tide of feminist thought. Interrogating the religious roots of ‘militancy’, it shows how the conception of suffragism as a spiritual struggle collapsed any easy distinction between ‘religion’ and ‘politics’, establishing prayer, worship and Biblical exegesis as weapons of political warfare. Using the League as a case-study, the article explores the wider relationship between gender ideology and religious thought, at a time when Christianity was the central referent of British culture. Activists preached sermons, wrote pamphlets and debated theology in the religious press, establishing a powerful theological case for reform. Inspired by the incarnational theology of Charles Gore, the League recruited over 500 clergy and eight bishops, convinced that enfranchisement was not merely compatible with, but actively demanded by, the teaching of Christ. It focuses, in particular, on the Church League for Women’s Suffrage, an Anglican organisation boasting nearly 6,000 members by 1914. This article shows how campaigners grappled with patriarchal readings of Genesis, St Paul and the traditions of the Church to construct a Christian case for equality. Its language and iconography were steeped in Christian imagery, yet the religious arguments for enfranchisement have rarely received close attention.

Looking back on the Edwardian suffrage campaign, the militant suffragette Annie Kenney thought it ‘more like a religious revival than a political movement’.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)